On June , 1990, Janet Adkins, a 54-year-old from Oregon, diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease drove to a Michigan parking lot with retired pathologist Jack Kevorkian. In Kevorkian’s makeshift “suicide machine” in the back of his rusty Volkswagen van, she pressed a button that released lethal drugs into her bloodstream. Her death launched a thousand debates and made “Dr. Death” the most controversial figure in American medicine.

In the late 20th century, a new movement began reshaping debates about the right to die, personal autonomy, and modern medicine. In the United States, the Hemlock Society—an organization founded in 1980 with the mission statement “Good Life, Good Death”—became the vanguard for assisted suicide advocacy, garnering close to fourty six thousand members at its height.

What Is Assisted Suicide?

Assisted suicide refers to taking one’s own life with the voluntary assistance of another party, commonly a physician who prescribes lethal drugs at the request of a patient suffering from a terminal or incurable condition. The practice is distinct from euthanasia, where a medical professional directly administers life-ending measures. Both, however, are designed to mitigate unbearable suffering and have sparked fierce ethical, legal, and emotional debates in societies worldwide.

The moral question underlying these debates—does society have the right to determine when suffering can ethically justify ending life—continues to divide communities, legislators, and courts.

Global Landscape: From Switzerland to England

The first nation to permit any form of assisted dying was Switzerland, legalizing assisted suicide as far back as 1942. Swiss law, unique in its latitude, allows non-physicians to assist in suicide so long as it is done altruistically, not out of self-interest. Public attitude in Switzerland has grown increasingly accepting: cases of assisted suicide rose from just 53 in 2005 to over 500 in 2023. The Netherlands formally legalized both euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in 2002, followed closely by Belgium and Luxembourg. The laws carefully regulate eligibility, typically allowing the procedure only for those suffering “unbearably without hope” and requiring medical oversight.

The most recent addition to this list being United Kingdom. The UK’s Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, also known as the Assisted Dying Bill, was passed by the House of Commons in June 2025. Other countries joining the legal movement include: Canada (2015), Spain (2021), Austria, Colombia. In the United States, assisted suicide is legal in a growing number of states, beginning with Oregon in 1994, followed by Washington, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine, and New Mexico—although active euthanasia remains illegal at the federal level.

The Ongoing Global Debate: Ethics and Oversight

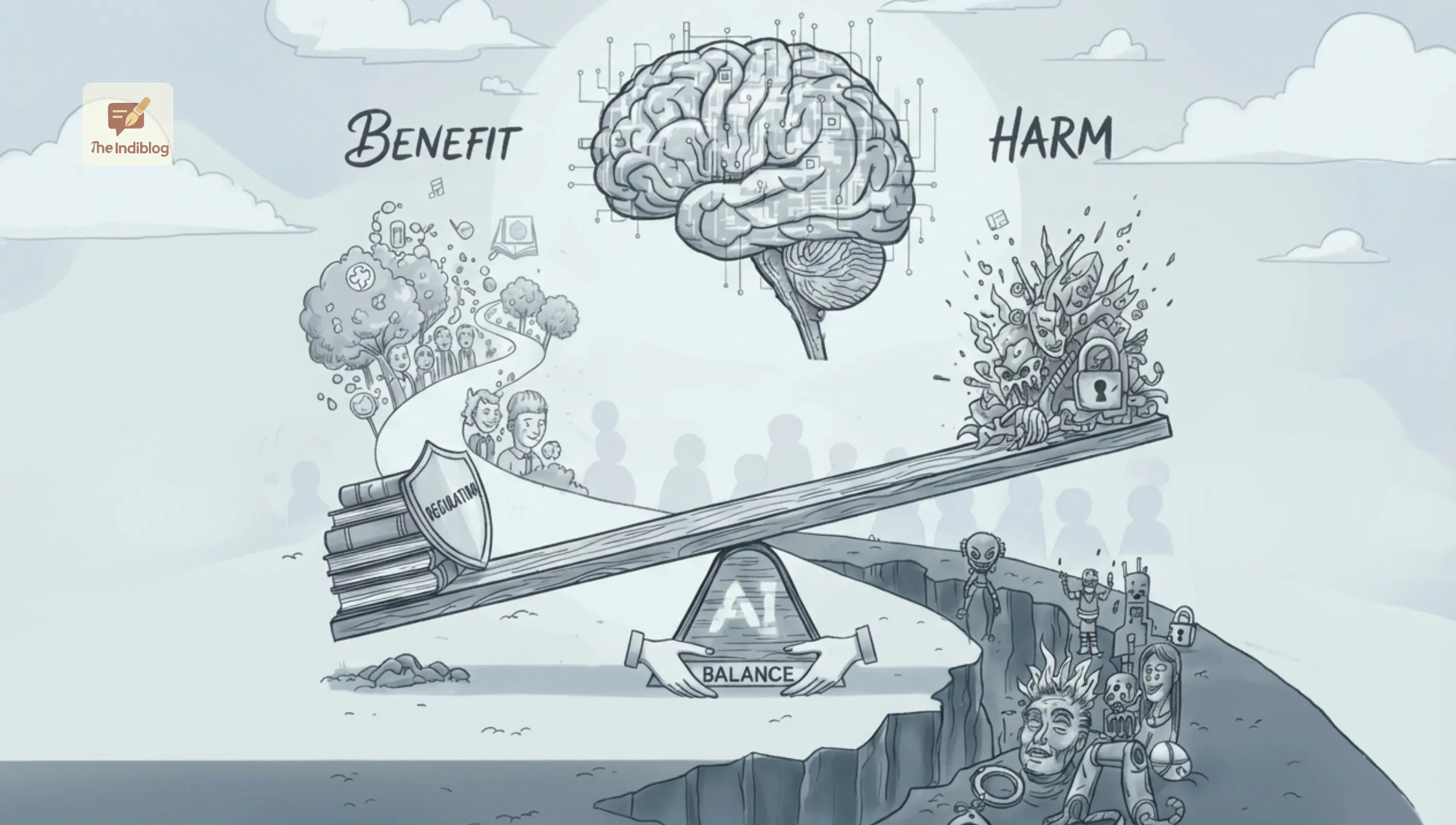

Despite growing acceptance, the divide over euthanasia and assisted suicide persists. For proponents, these laws represent autonomy and relief from unendurable pain—a shift from preserving life at any cost to prioritizing quality of life. Critics warn of risks to vulnerable populations, potential coercion, and slippery slopes between legitimate assisted suicide and murder. Legislative frameworks worldwide attempt to draw safeguards: eligibility tightly controlled, mandatory medical oversight, psychological evaluation, and often court authorization.

India’s Legal Position: Passive Euthanasia Allowed, Active Banned

India’s stance on euthanasia and assisted suicide is more conservative. Active euthanasia and assisted suicide remain criminal offenses under the Indian Penal Code, which broadly prohibits any act amounting to intentional killing—even with consent. However The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita does not include an equivalent clause to Section 309 that criminalized attempted suicide in India, hereby attempted suicide was officially decriminalised in India through the introduction of BNS. Yet, in a landmark case, India’s Supreme Court created a pathway for passive euthanasia—the withdrawal of life support for terminally ill patients under exceptional circumstances, with strict supervision.

The Aruna Shanbaug Case: A Watershed Moment

The debate accelerated in 2011 with the highly publicized case of Aruna Shanbaug, a nurse left in a vegetative state following a violent assault in 1973. Activist Pinki Virani petitioned the Supreme Court for passive euthanasia—a plea ultimately rejected on medical grounds. However, the Supreme Court’s decision set a monumental precedent: it acknowledged passive euthanasia as permissible in select scenarios, if requested by family and approved through court and medical supervision. This ruling ushered in a measured, cautious approach; while active euthanasia remains forbidden, passive euthanasia is now guided by strict legal protocols.

The Thin Line: Dignity, Autonomy and Abuse

Should India follow other nations in legalizing active euthanasia? The question is fraught. India’s legal system operates amid massive population diversity and uneven access to justice. Advocates warn about risks of abuse—where power, money, or social pressures could tilt decisions away from genuine autonomy toward coerced death or concealed murder.

India also faces staggering suicide statistics. In 2022, the country recorded 171,000 suicides—the highest number globally—at a rate of 12.4 per 100,000, a grim record unmatched by any other nation. Experts attribute this public health crisis largely to untreated depression, economic despair, and social alienation. Official data hint at thousands of unreported deaths—especially in remote or marginalized areas—where neither the media nor police reach. The specter of normalized or privileged murder under the guise of euthanasia remains a concern for critics of legalization.

The Politics and Public Opinion: Lawmakers, Polls, and Social Change

Globally, shifts in public attitude have driven legal change. Support often springs from personal stories—families confronting terminal illness, or high-profile cases challenging laws. Yet, polls remain contentious. While support for euthanasia and assisted suicide may be high in some countries, allegations of political manipulation, ethical misgivings, and the weight of religious doctrine continue to shape the discourse. In India, recent legislative proposals—the Euthanasia (Regulation) Bill, 2019—sought to provide more clarity and safeguards, but remain unpassed, leaving active euthanasia in legal limbo.

With passive euthanasia now legal, India stands at a crossroads. The legal framework—the requirement for court and medical review—aims to minimize risk of coercion and uphold patient dignity; yet critics say it is cumbersome and inaccessible for many families facing end-of-life agonies. Both public health data and ethical arguments underscore the complexity of India’s scenario. With the highest suicide numbers globally, yet limited mental health care and massive social disparities, any move to expand assisted suicide provisions would require robust safeguards, public education, and transparency.

Cautious Steps Forward:

As the world contends with the weighty question—Who has the right to decide when life should end? —India’s debate remains deeply complex. The promise of autonomy and dignity for the terminally ill is compelling, but the risks of exploitation are real.

Global trends suggest that legislation must marry compassion with rigorous checks. For India, the lessons from other nations—tight requirements, court oversight, clear medical protocols—suggest a path forward that could balance patient autonomy with social vigilance. The shadows cast by high suicide rates and historic abuses mean that, for now, caution outweighs zeal. The moral, legal, and medical debates will only intensify. But in the search for a ‘good death,’ India must first secure a system that guarantees a good life—including mental health support, strong legal protections, and equal access to justice.

Assisted suicide and euthanasia will remain contested spaces, as they should, in every society that seeks to balance autonomy and ethics, compassion and caution, dignity and the sanctity of life.